I really love watching videos or reading articles where the author makes the topic of white balance sound like something requiring decades of wizarding school and a willingness for blood sacrifices. The concept of white balance is very simple so I’m going to try and clear this up for everyone as quickly as possible.

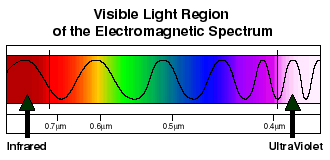

We have these marvellous things called eyes. Our eyes see a very wide range of the electromagnetic spectrum, the portion we see euphemistically called light. The spectrum is much grander than what we can see and includes infrared, ultraviolet, gamma, radio, microwave and many other classifications of emissions. For our purposes, we are going to focus on the narrow band that we see.

Envisage if you will, the famous cover of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon by the talented graphic artists at Hipgnosis. We recall a spectrum from science class perhaps of a rainbow running from red to violet.

Visible light. Image Credit: NASA

Humans don’t see infrared or ultraviolet in general but it’s included in the graphic for information purposes. The graphic also expresses the wavelength of light of different colours numerically. A longer wavelength has a shallower curve from crest to crest, where a shorter wavelength has a sharper curve from crest to crest, thus we can see that violet light has a shorter wavelength than red light. Bound to the colour of the light waves is the idea of the colour temperature of the light waves.

Unfortunately, our human perceptions create confusion because our perception is actually the opposite of reality. For example, if you go outside on a cold winter’s day with heavy cloud cover, and I asked you what colour the light is, you would most likely say it was bluish. If I asked you to describe the light of a sunset whilst on a beach you would say it was orange. If I asks you to associate a temperature with the colours you would say blue associates to cold and orange associates to warm. We feel this because we have generations of experience associating orange with fire and therefore warmth, and blue with ice and therefore cold.

It works for us as humans but is backwards when it comes to colour temperature. A professional welder will tell you that the blue flame is much hotter than a red flame, but this is an exception to our usual perceptions even though our language is peppered with accuracy such as the association that white hot is much hotter than red hot. Because welding involves using high temperatures to join together metal pieces or parts to the point of melting using a blowtorch, electric arc, or other means, and uniting them by pressing om hot ering, metal, are s well as theproessentialfessionou ake sy within safety compliance. As any professional welder who is familiar with welding and construction equipment such as a Badass MIG welder will admit, welding is not for the faint-hearted.

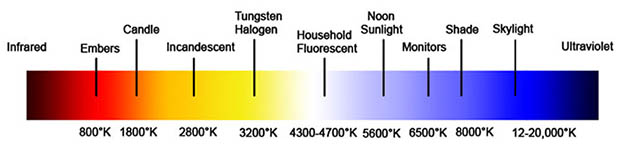

In the visible spectrum, the longer wavelengths of light are colder than the shorter wavelengths of light. This is why so many folks get confused. We associate orange with warm and then learn that the colour temperature of a candle flame is 1800 degrees Kelvin. That’s the colour temperature, not the flame temperature. (Why that’s so is a much deeper conversation better suited to a physics class). We think of that as warm. Then we learn that it’s actually quite cool in the range of colour temperature and it messes us up. In the chart that follows we see a range of colour temperatures matched to common emitters.

Emitters and Colour Temperature. Image Credit: Lowel-Tiffen

As we look at this chart we start to see common white balance settings in our cameras and we learn that the Shade setting corresponds to a very blue and relatively high temperature. Similarly, we see that the “warm” light from a tungsten bulb is actually relatively cool at 2800 degrees Kelvin.

Make it easier on yourself by thinking most about the colour and less about the temperature. A White Balance setting of Shade corresponds to the colour of light in shade. A White Balance setting of Fluorescent corresponds (mostly) to the colour of light in a fluorescent illumination scenario. Simply match the light source to the White Balance option and set that. In addition to Automatic, most cameras today offer Daylight, Cloud, Shade, Fluorescent, Tungsten, Flash and one or two Custom settings. Custom settings are most commonly used with tools to help you set a specific white balance for a specific source at a specific time. We will look at tools like this in a future article.

It’s also reasonably well understood that when shooting in RAW, the White Balance setting really doesn’t matter because the image needs processing once out of camera. However, setting the white balance properly in camera will make the image on the LCD look better and provide you with a better starting point in your editing.

If you are shooting JPEG, it is much more important to set the white balance correctly in camera, because whatever you set gets cooked into the image right on the card and while you can make changes in post, you lose some latitude in doing so, because of the data loss that occurs in the JPEG compression.

Lots of photographers select AWB (Automatic White Balance) for everything and leave it there. This is hardly fatal because AWB works very well around 90% of the time. When you have mixed sources of different colour temperatures it tends to throw up its hands and give up, so it’s in your best interest to take a few seconds, look at the scene, choose the closest white balance setting that you think fits and set it. It’s a heck of a lot easier than the old method of adding colour correction filters to our lenses to match the light to the colour sensitivity of the film being used.

There are wonderful tools that can help you achieve “proper” white balance when you get an image into your processing software and a future article will look at the ones that I use and prefer, but even if you don’t use such tools, making a good setting at time of image capture will take you a long way to success without spending any more money.

Until next time, peace.