This time we are going to talk about a really powerful – but occasionally misunderstood – flash tool called HSS, or High Speed Sync.

Figure 1: High Speed Sync allowed this image to be made outdoors in bright sun and let the flash overpower the sun and the ambient light.

What are Sync and Sync Speed?

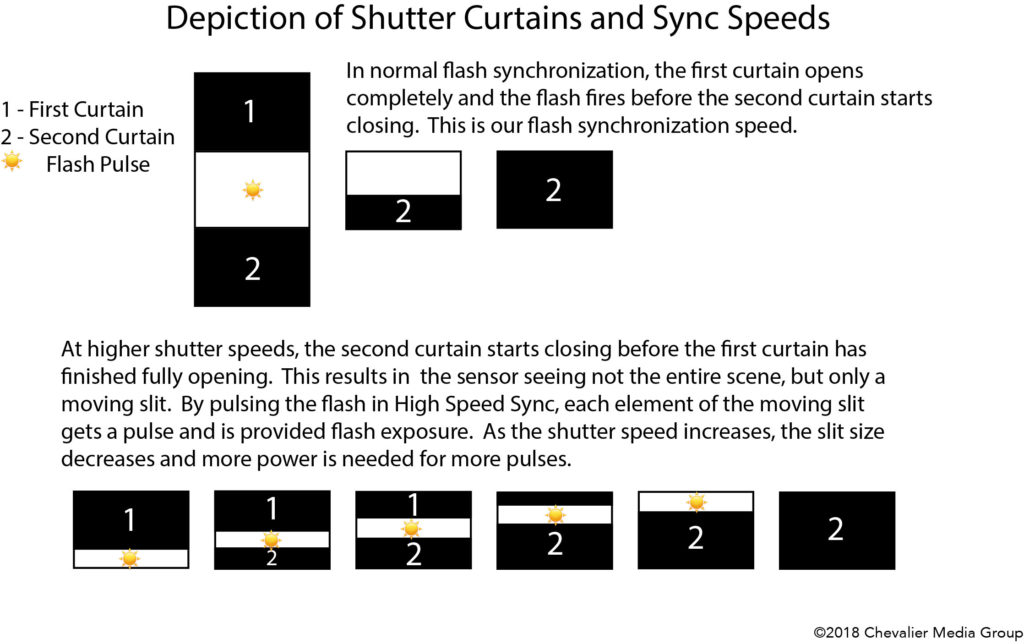

All cameras, with the exception of those using lens shutters, have what the maker calls the flash synchronization speed. We understand that a camera focal plane shutter has two panel sets called curtains. Shutter speed determines the length of time between the opening of the first curtain and the closing of the second curtain. With long shutter speeds, let’s say a one second exposure, the first curtain opens completely, and the sensor is exposed to light for one second and then the second curtain closes. As we increase the shutter speed we decrease the time between open and close. At some point in every shutter, the second curtain starts closing before the first curtain finishes opening. At this shutter speed and higher, the shutter opening is no longer the size of the full sensor but is now a moving slit. Thus, the maker defines the sync speed as the highest shutter speed which allows the first curtain to open completely, before the second curtain starts to close.

Is This a Problem?

For the majority of flash scenarios, the sync speed is not a problem because we can typically find an exposure that is going to work for our flash at or even below the camera flash sync speed. Today’s cameras typically have a flash sync between 1/200 and 1/250 of a second. However, you may have seen images where the shutter speed was set too high, without High Speed Sync engaged, resulting in images that had a black band on them.

When It Becomes a Problem

Now let’s suppose that you have a lens with a really large maximum aperture, permitting incredibly shallow depth of field, such as an f/1.4 capable lens. You want to shoot outside, but you use flash and light shapers to take full control of the light whether to fill, match, or overpower the sun.

If we use the example of a bright day with direct sun, we know that the light on a portrait is going to be harsh and with strong shadows. This is the worst quality of light that we may have to deal with for weddings, engagements, and family events. So rather than get lousy images, we want to fix things, and that means flash.

The problem in this scenario is that a base exposure is going to be something like 1/250 of a second at f/11, ISO 100. We want to throw the horrible background out of focus, so we open up to f/2.8. This raises our shutter speed to 1/4000 in order to maintain a proper exposure just to handle the ambient light. Unfortunately, at this point, the shutter opening is a moving slit and regular flash is not going to work.

In order to illustrate this, I asked my very photogenic model Sondra to help us out. Sondra can hold a pose forever.

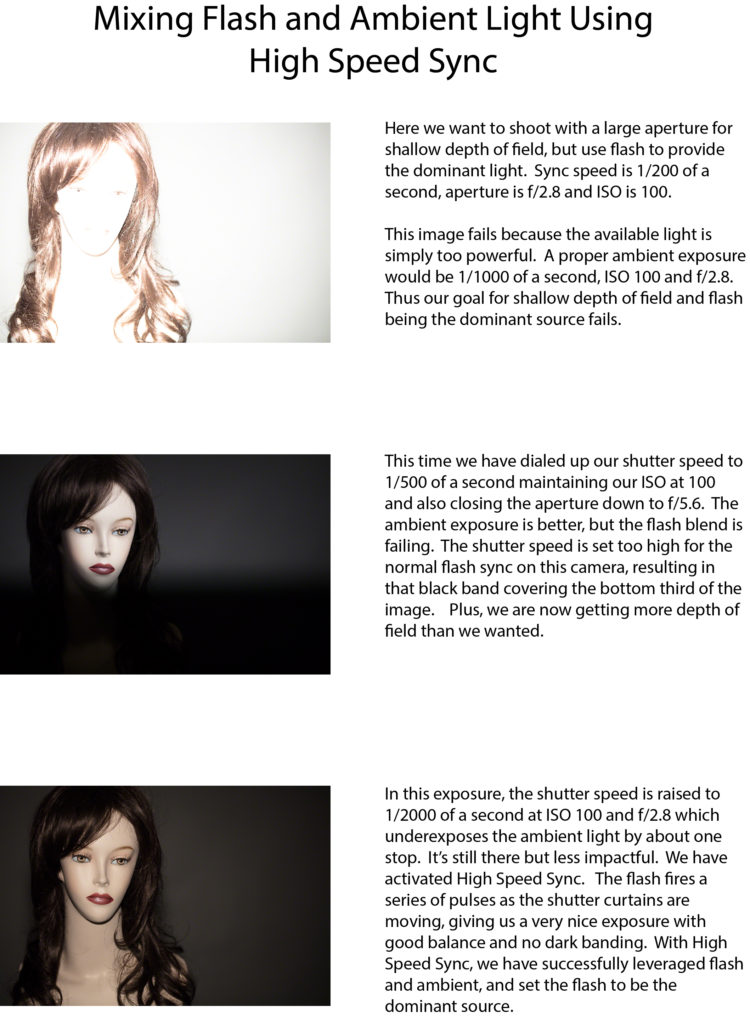

My first exposure was to try to get the flash to match the ambient, but the flash sync speed in the camera that I was using was 1/200. I wanted f/2.8 for my aperture so that I had nice shallow depth of field and I wanted my lowest ISO of 100.

The camera meter told me that this was not going to work. It proposed a shutter speed of 1/1000, but as soon as I turned the flash on in the hot shoe, it forced my shutter speed to the standard flash synchronization speed. As you’ll see, the resulting image is far too bright because the flash exposure was completely overridden by the much brighter ambient light.

I raised the shutter speed to 1/400 to see if that would help and also closed the aperture down to f/5.6 in order to get the ambient in line with the flash. While the ambient is coming in line, the flash sync is too fast. The second curtain has already closed partway when the flash fires, resulting in that black band. I’ve also now asked the flash to work harder, and increased depth of field, when I did not want to do so.

In my final shot, I activated High Speed Sync. I knew I wanted shallow depth of field, so I went back to f/2.8. I knew that the ambient light wanted a shutter speed of 1/1000, but I wanted that underexposed to make the image of Sondra pop off the background. So, I decided to set the shutter speed to 1/2000 of a second. Without High Speed Sync, the second curtain would be closed before the flash fired and I would get an underexposed ambient light only shot. With High Speed Sync, the flash fires a series of pulses as the shutter curtains are moving, resulting in a lovely exposure on her face, while the background (ambient) is underexposed, making Sondra pop.

Figure 2: Outdoors, lots of ambient light, but I wanted very shallow depth of field and to downplay the background. High Speed Sync makes this possible.

This set of images was shot with the flash on camera, pointed at Sondra, with the flash diffused by a MagMod MagSphere.

How High Speed Sync Works

Not all cameras support High Speed Sync, but most modern cameras do. You also need a flash that supports High Speed Sync. Most OEM and a large number of third party flashes support High Speed Sync as well. If your systems do, you have a solution.

In High Speed Sync, instead of a single pop of light, the flash fires many pulses to fill in the slit as it moves across the focal plane. This feature allows us to achieve a proper flash exposure at a shutter speed much higher than the default flash synchronization speed. It’s absolutely brilliant and on many camera / flash combinations that support High Speed Sync, it’s often just a switch setting.

Now in our example, we could set the shutter speed to 1/8000, the aperture at f/2.8 and the ISO at 100 and use the flash as our main light and actually underexpose the ambient light to beautiful effect. With High Speed Sync, you are the master of the light, not the consumer of whatever gets hurled at you.

Downside

The primary downside of High Speed Sync flash is lack of range. All those pulses take up power, and the more pulses needed, the less power is available for each pulse. The flash manages this itself, but this reduction in power per pulse will limit flash range and minimum aperture. In our example scenario, we are shooting at a large aperture, which gives us much more latitude in terms of distance than f/11 would have. In fact, over the five stops, this means 32 times the power is available for distribution. Once you understand the range limits, you are in good shape.

Summary

High Speed Sync is a huge benefit to all photographers who want to make the best images possible, and particularly so, if you are looking to balance or beat the ambient light during daylight. You will find that most flashes that deliver a high output support High Speed Sync. A flash that is low powered in its normal operation is not likely to help you much because of the distance limits created by the lower powered individual pulses.

When looking to add a flash to your kit, check to see if your camera supports High Speed Sync. If it does, make sure that the flash you are looking at supports High Speed Sync and that it is a very powerful unit.

Have you tried High Speed Sync? How did it work for you? Share your experiences in the Comments, and your questions on this or any other subject.

Until next time, peace.